March 13, 2019

There’s a Better Way to Manage Human Waste

contributor: Pallavi Bharadwaj

I come from the highest caste of Brahmins in India. India has always been a caste-based society, historically divided into Brahmins (the priests), Kshatriyas (the warriors), Vaishyes (the traders) and Shoodraas (the untouchables). Growing up, I saw the sweepers’ families come in every morning to clean our household latrines, as it was considered a ‘dirty’ chore for my family members. These latrines were outside our main house, so that the sweeper and his family didn’t have to enter or see our main living space.

I was adopted and brought up by a grandparent who abhorred this practice. He cleaned his own latrine, and taught me to do the same. He explained to me how ridiculous this idea of caste system was, and how our abolishing this practice as an entire society was long overdue. This led me to think long and hard about the type of jobs that people were ‘supposed’ to do based on their castes in India, and how I could contribute towards making a difference through my work in global development.

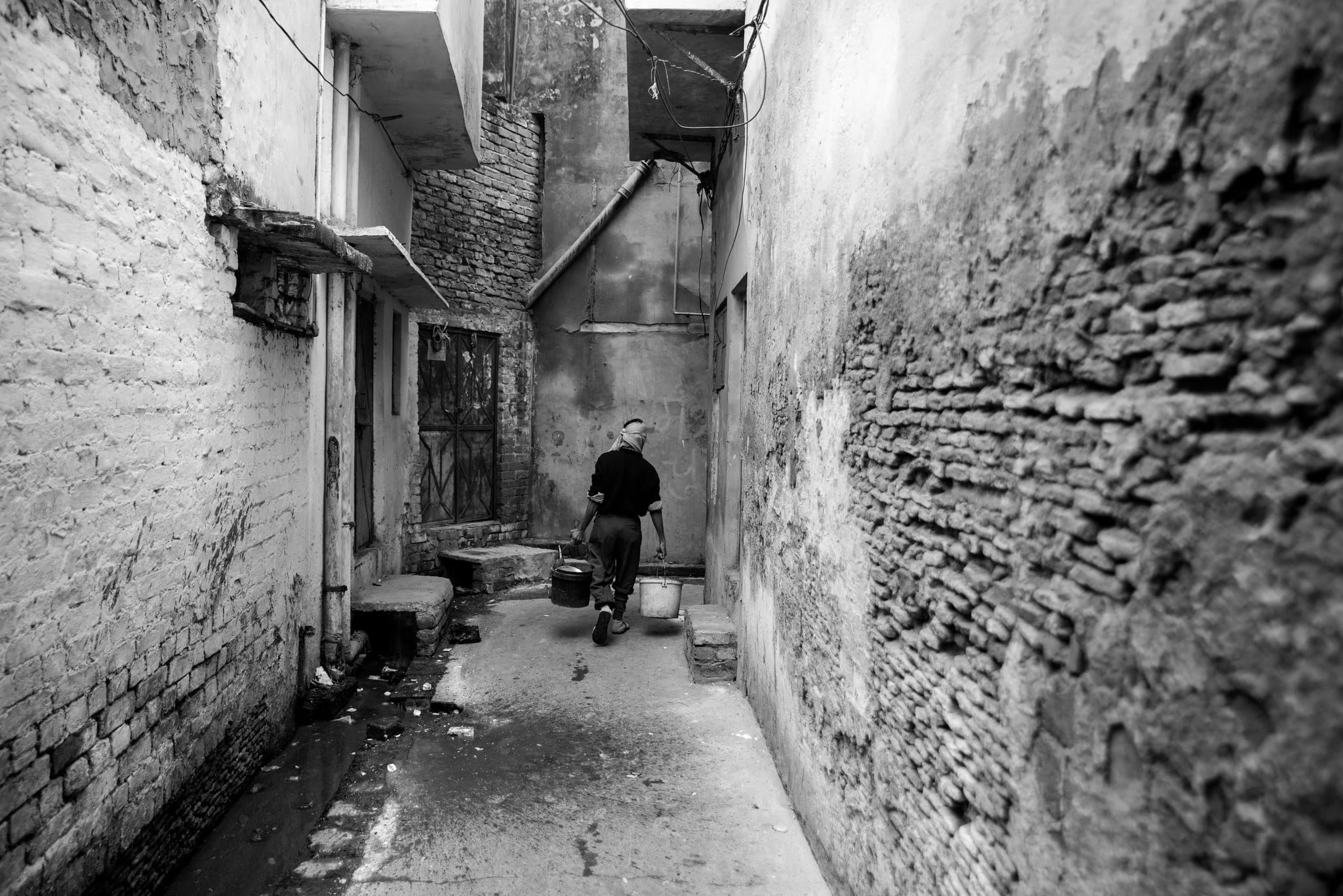

Sadly, from India all the way to Kenya, the practice of manual scavenging, as the dirty clean-up work is called, is still fairly common. Despite the practice being banned since 1993 in India, the news of sewer deaths are not rare. A non-governmental organization that advocates for manual scavengers, Safai Karmachari Andolan, says that the practice led to 429 deaths in Delhi alone from 2016 to 2018, as reported in Sabrang India.

In addition to loss of human life, the untreated sewage poses myriad threats to drinking water quality, human health and the environment. In Kenya, more than half of the urban population lives in informal settlements like Kibera, which houses about 250,000 people. The waste they generate flows untreated into the Nairobi river, which ultimately finds its way into the Indian Ocean.

Globally, almost 80 percent of the world’s wastewater flows back into the ecosystem without proper treatment. This means that almost a quarter of people drink water contaminated with human waste, according to United Nations Water. That incubates deadly diseases, including cholera, dysentery, typhoid and polio.

Engineering for Change’s Solutions Library features a number of safe disposable solutions for human waste, such as Laveo dry flush toilet, savyyloo, clivus multitrum composite toilet and others. In addition to these products there are also services that could provide a way to generate income, such as Clean Team, Sanivation and Sanergy models.

March 22 is World Water Day with ‘Leave No one Behind’ as the slogan for 2019. Only by addressing these challenges, providing solutions and gainful employment to the service providers, we can work towards achieving the SDG 6-Clean Water and Sanitation for All and #leavenoonebehind.

Rajan, a resident of Lucknow in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, carries buckets of refuse from latrines he cleaned. Rajan, of the Valmiki caste, is from a family of scavengers and inherited his job at age 14. Photo: Sharad Prasad (CC BY 2.0)